By Hannah Onstad Sarah Cooper is a keen observer of the artifice that passes for knowledge in our culture. As a comedian, she’s provided a besieged country with much needed comic relief by posting Trump parodies which simultaneously expose the vapidness of his speech, his white-male entitlement, and the country's systemic racism and sexism. Plus, she’s managed to do all that and hit more than 10M views on YouTube, while shooting a low-budget production at home—at a time when much of late night television struggles to stay fresh during lockdown. Inspired by and delivered first on TikTok, Cooper lip syncs to Trump speaking, which works viscerally by showing us how we would normally judge Trump’s statements coming out of any other person's mouth. The comic impact of the joke is in the disconnect between hearing the supposed leader of the free world’s bewildering speech while watching a woman deliver the words with false bravado—like he often does. Cooper manages to amplify how ridiculous Trump sounds—something traditional reporting and transcribing has tried and failed to do, instead only amplifying his message. Reporters have written about the challenge of reporting on Trump’s speech and have certainly detailed how linguistically challenged he is. Yet, as a comedian, Cooper helps us hear Trump's incoherence by stripping away his carefully crafted image, supplanting it with her own, and thereby creating just enough distance to force us to scrutinize his words in a fresh new way, exposing them as thoughtless and even dangerous. With a country facing a pandemic, widespread systemic racial injustice, and economic uncertainty, Cooper proves that Trump is as fit for the presidency as a cymbal-banging monkey. Through watching Cooper’s clips, we also learn more about how Trump maintains his illusion of authority—through gesture, posturing, and self-aggrandisement. She emphasizes, rather poetically, how he masks his empty words with the gumption of his delivery. It is through her imitation of this hubris that the facade of Trump’s leadership-schtick cracks and falls away completely. This is not Cooper’s first parody and she has honed a keen eye for calling bullshit in the corporate world, (she is a former Google employee), pairing searing insights with inspired graphics as in 10 Tricks to Appear Smart in Meetings which turned into a bestselling book 100 Tricks to Appear Smart in Meetings. In a recent appearance on The Ellen Show, Cooper said in reference to Trump, “The stuff he gets away with saying, I could never get away with saying.” And she’s right: Trump couldn’t make it past HR in most corporate settings. He’s so isolated from reality, so insular, he hasn’t been able to adapt to the changes and advancements society has made. Increasingly, as more voices speak out—black people, immigrants, women—they are forcing Americans to reckon with how white males often get away with doing things the rest of us could never get away with doing. Trump’s sloppy elocution shows just how devoid of ideas he is, yet his racism and sexism comes through loud and clear. From his creepy comment about being able to assault women to his even more disturbing rumination about being able to stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, to his cavalier use of force against peaceful protestors. Without white male entitlement to prop him up on Trump would just be an angry, creepy Grandpa shouting at a television. From the horrific murders of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery and so many others, to the sexual predation of Harvey Weinstein, Jeffrey Epstein, and scores of Roman Catholic priests, to the wave of young disaffected men who have committed mass murder in their schools with guns, Americans know and have seen “a male-dominated culture that presents dominance as a natural right” as Gloria Steinem famously wrote in her 1999 essay titled “Supremacy Crimes.” The concept of Supremacy Crimes shows what happens when white male entitlement to dominance is not checked. It is only within the context of deep racism and sexism within our country, that we understand how some white males have taken their privilege and used it to dominate and exploit others. It is also within this context where we see how white males have historically protected other white males from consequences for their behavior. Trump simulated this act of dominance while playing a role in his reality TV show, The Apprentice, using symbols and signs to construct his authority over others. Cooper’s parodies of Trump wind up being a meta-reflection on white male power and authority, a simulacrum of the same acting. Through that lens, we see the natural injustice of who we allow to speak, and who we are forced to listen to in our society—blowing the myth of American meritocracy up. Trump has gotten away with being incompetent. We as a country have resigned ourselves to the insult of his speech, partly because we’re primed to do so, having already endured and accepted so much white male entitlement in our culture already. That is, until others speak up. This is why I love Sarah Cooper—her humor is the sharpest political tool we have. She’s earned a mic drop.

0 Comments

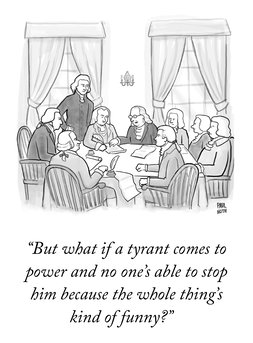

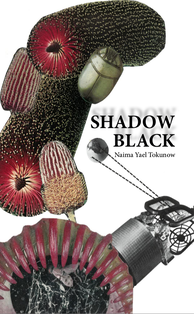

This week, on June 1st specifically, I felt more than just uneasy. I began to feel downright panicked. My son and I surveyed our neighborhood and more businesses have closed or boarded up their windows. Escalation between protesters and some police continued. Helicopters flew overhead each day. COVID-19, already an unprecedented pandemic that has left more than 100,000 Americans dead, is now overshadowed by political unrest. The evidence of the senseless killing of people of color in police custody without immediate justice made the weight of these times practically unbearable. Among the worrisome new developments: - Peaceful protesters were attacked, including dispersed by tear gas and shot at with rubber bullets in D.C. to make way for a pointless photo-op. - The so-called "commander-in-chief" issued a directive to "dominate" the protestors, followed by a call to occupy the "battlespace" from his military top brass. This aggressive and militaristic language is inappropriate to the situation and the constitutionally-protected right to peaceful protest. - Then then the unpopular president called "antifa" is a terrorist organization (antifa literally means "anti-fascist" and the alternative must be what the president embraces...fascism). - Finally, a bill to condemn lynching failed to pass the Senate in 2020 in the United States of America. More than 20 years ago, Gloria Steinem wrote an essay titled "Supremacy Crimes" and what she wrote then is as, if not more, important today. Steinem's essay focuses on the fact that most “impersonal, resentment-driven, mass killings” are committed by white, non-poor, heterosexual men. Steinem's prescient essay gets to the heart of the brutal treatment of people of color, the deaf ears to cries for justice, and the stubborn fact that white males are raised to feel entitled. Writing in 1999, Steinem said: “White males—usually intelligent, middle class, and heterosexual, or trying desperately to appear so—also account for virtually all the serial, sexually motivated, sadistic killings, those characterized by stalking, imprisoning, torturing, and “owning” victims in death.” She names the concept of "supremacy "as the culprit that routinely allows these sorts of crimes to occur stating it's a “drug pushed by a male-dominant culture that presents dominance as a natural right; a racist hierarchy that falsely elevates whiteness; a materialist society that equates superiority with possessions, and a homophobic one that empowers only one form of sexuality.” In the midst of a chaotic week of racial tension, I watched a a video clip of Senator Kamala Harris make an impassioned plea on the Senate floor to finally pass an anti-lynching bill. I later learned that the bill had stalled due to the "private objections of one Republican, Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky, who has succeeded for months in preventing it from becoming law." One would be right to wonder how one man could stand in the way of such an obviously needed piece of legislation at a time like this. And one would be further justified in thinking it unreal that an entire nation of protests is not enough to pressure this one white male into doing the right thing. So, what we see is a culture that is producing adult white males who feel justified in carrying out acts of violence against people of color; young white males with guns who have taken their frustration out on unarmed innocent people; and the prevention of laws to stop all this by powerful white men in government. It's enough to drive one crazy from grief and anxiety. The antidote to this may be to turn to the people who's voices do matter but who may go unnoticed in a news cycle such as this—the writers, poets, artists, entertainers, and activists who are addressing our collective nightmare and offering us their work. IN the coming weeks, I hope to feature some of them on this blog. Today, I have been reading a chapbook of just-published poetry titled Shadow Black by Naima Yael Tokunow. Tokunow writes poems that are both searing and sensitive. Reading her words provides a deeper, visceral understanding of what it means to live in a culture that allows supremacy crimes to proliferate. "I always thought my pretty would save me flash dimple and toss hair and not die and maybe it’s shameful to say that out loud because every black body moments before becoming dead was exquisite and they weren’t saved" — Naima Yael Tokunow So far, 2020 has been a time that calls for us all to reflect more deeply on what is happening all around us. Art can help us in this moment. Maybe art cannot solve all of our problems, but it can slow us down and help us process, understand, and make meaning of the onslaught. Shadow Black is one notable work that shows us the way. Shadow Black is published by Frontier Poetry and is available as a free downloadable chapbook from their website. Copyright © 2020 Naima Yael Tokunow Supremacy Crimes was excerpted from: Joy Ritchie. “Available Means.” Apple Books. https://books.apple.com/us/book/available-means/id911935639  By Hannah Onstad While its contours remain the same, the activity on my residential street is changing. What's salient about the street is that it is flanked by fourteen majestic Chinese elms that drip long, willowy green fronds which form a canopy partly obscuring the sky. In the spring and summer, when the small green leaves burst forth with exuberance, it makes this otherwise ordinary block of Northern California feel more southern and gothic, slow and sultry, like Savannah. The fronds sway gracefully in a light breeze and hang like Weeping Willows, but do not reach the ground, instead they dangle just above the heads of passersby from hefty limbs emanating from their trunks which reach skyward like outstretched arms. The tops of these 100-year old trees tower a story taller than the houses, and their wood is considered the strongest of the elm genus, making them not just de facto giants, but meritorious elders, the would-be rulers of their kingdom, our humble block, should they be given their rightful due. On this otherwise ordinary street, the surface is rough though free of speed bumps and potholes. In one direction it leads to a T that snakes deeper into the residential neighborhood, and in the other direction it is two blocks to a main artery of traffic. It was once bustling with activity and now, maybe every 10 or 15 minutes a car drives by, rarer still would be two cars passing one another. While there are fewer cars passing now, you do see more white vans and delivery trucks double-parked, the soft fronds from the trees licking and draping over the tops of the trucks. The drivers leap out and walk gingerly to the rear, rummage inside the open doors to retrieve packages—boxes, bags, food containers—and walk them up to one of the front doors. Knocking once and then dispensing of them, leaving the packages on a chair out in the open, or barely hidden behind a large planter. Sometimes doors swing open a moment later with furtive waves and a call of thanks from the safety of the house and vehicle. Other times the packages sit and await retrieval. The frequency of the double-parked vans and trucks on the street is one of the signs the pandemic is altering life on what was once called Cherry Street. Another is the wave. At 10am each morning, neighbors, a smattering—and it’s a different smattering each day—open their doors and shuffle outside to look up and down the block to see who else is out. Then there’s a wave, and maybe a shout out to one or another to inquire about how they’re coping, maybe a brief exchange of news. The neighbor across the street is tall and blonde and always opens the door with a toddler on her hip. Two doors down from her, our neighbor, the festival organizer, complains of the uncertainty of planning her annual seven-stage gig in the park this year. Another retired neighbor, joins from down the street edging closer, but not too close, with a walking stick. Then after a minute or two we all shuffle back inside. It’s a simple opt-in, no pressure gesture that makes us feel a bit more connected as we start another week of shelter in place. I've noticed more joggers lately too. They tend towards the middle of the street now that there's less frequent traffic from cars. When people do walk down the sidewalk, they cut a wider berth around each other when they pass. The trees though seem impervious to our plight. They are the apotheosis that seem to suggest that while human behavior may be altered, the contours of the block remain largely the same. This interview originally appeared on AlterNet.

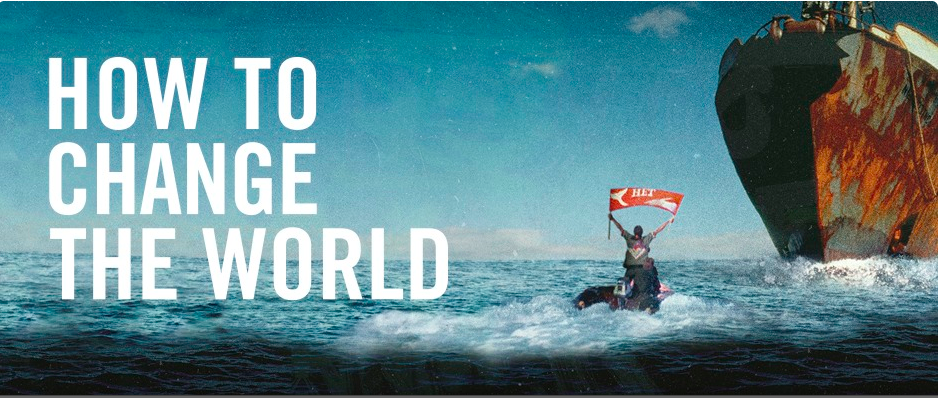

Annie Leonard, executive director of Greenpeace USA, answers a few burning questions. Interviewed by Hannah Onstad The Arctic is melting. The planet is recording the warmest weather on record. The environment is in dire straits. By many accounts, it’s already too late. Yet, we’re on the eve of some of the most important worldwide climate talks. Will the gravity of our predicament finally wake us up and into action? We asked Annie Leonard, executive director of Greenpeace USA, a few burning questions. Hannah Onstad: Has the environmental movement failed, given there’s still ongoing debate and skepticism about human-caused climate change? Annie Leonard: There’s nothing failing about the environmental movement right now. Look at what we’re achieving: Shell just quit its Arctic drillingprogram. Obama just withdrew the option for any oil company to go drill in the Arctic for the next two years. He’s poised to reject the Keystone XL pipeline. None of these things would have happened without today’s vocal, diverse, dedicated and growing movement. At the same time, the clean energy revolution is happening. Solar and wind power are now growing way faster than electricity generated by fossil fuels. All this doesn’t mean that we’ve won yet. We’re still very much in the thick of it. There’s lots of empirical evidence all around us that things are getting worse — and there’s lots of evidence we’re making progress. The final act hasn’t been written yet. I remember learning about climate change in college in 1982; no one was talking about it then. Now we have schoolchildren, artists, indigenous people, farmers, business leaders and elected officials speaking up, planning protests, making progress. Look at the upcoming meeting of global leaders in Paris on climate change! I have never seen such widespread public tracking and desire to engage in a UN conference — but that is because people increasingly know what’s at stake and want to help determine our future. HO: You’ve been at the helm as executive director of Greenpeace USA for just over a year now and yet many people know you from your successful video series The Story of Stuff Project. Given your experience with the media, how do we get people to think about climate change as much more than an environmental issue and one that affects everyone? AL: Community organizer Saul Alinksy urged us to talk to people where they’re at, not where we’re at, and that means we have to start by listening. Climate activists and communicators who have moved beyond throwing incomprehensible or depressing data at people are making great strides through storytelling, narratives and even art. Climate change touches so many things in our world. Whether you’re concerned about your children’s health, passionate about local food, worried about job security, interested in building design — or really just about anything — there’s a climate connection. HO: What happens if a climate-denying Republican gets elected in 2016? AL: It’s clear that much of our Congress has already been captured by the fossil fuel industry. Koch Industries, ranked the 13th biggest polluter in the U.S., has spent over $22 million on federal political candidates since 1999. This is a huge problem, because it means that our democracy, which should be the best tool we have to advance solutions, is paralyzed. That’s why Greenpeace, along with a growing number of other environmental groups, is increasingly focused on getting corporate money out of our elections, and out of government more broadly (things like regulatory advisory groups, “expert” commissions, etc.), which is crucial to advancing climate solutions. I make a point of starting every day feeling hopeful, otherwise it would be really hard to do the work I do year on year. So I believe this country will do better by our kids, and their kids than to elect a climate denier into office. But if it does, that’s all the more reason to keep building this incredible people’s movement that’s already underway. HO: Many people still associate Greenpeace with saving the whales (as explored in the recently released documentary How to Change the World: The Revolution Will Not Be Organized), yet climate change is much harder than saving the whales. How do you attack a much more complex issue? AL: Our history campaigning for whales has led to decades of experience in direct action and peaceful protest. But the drivers of climate change are complex and systemic, coming from many places at once. That’s why our solutions must be too. Greenpeace is well equipped to take on complex — or what some scientists call “wicked" — problems. We are working in 55 countries with a major presence in every one of the world’s top carbon emitters. Even in mainland China, where freedom of speech and the ability to protest are severely restricted, we’re doing incredible work to highlight the health effects of coal pollution on the Chinese people, and encourage global businesses to champion the switch to renewable energy. HO: Greenpeace used to get publicity and be in the news regularly, but not as much anymore. How potent is Greenpeace now? And will it have to change to be relevant in the climate fight? AL: I have to disagree with you that we’re not as much in the news anymore! We’ve had some of the biggest stories in Greenpeace’s history over the past couple years. Our campaign to Save the Arctic has helped bring together a global movement of millions. Two years ago when 28 of our activists and two journalists were arrested in Russia for a peaceful protest at Gazprom’s oil rig, the story was in the spotlight for months. Heads of state from Brazil to Germany stepped in to help free the activists; even Paul McCartney wrote personally to Vladimir Putin! That said, organizations have to change constantly to stay relevant and to keep learning. We’ve been using new technology like drones, for example, to expose the massive underground peat fires burning across Indonesia. A Greenpeace drone recording the effects of drought in Brazil's Serra Azul dam reveals that the water crisis is just beginning. (image: Greenpeace Brazil/Flickr) One area that’s particularly important to me in terms of learning is efforts we’re making to be a good partner to other organizations and allies across the movement. The incredible protests against Shell’s Arctic drilling this summer — which also got a ton of news coverage—are a great example of that. It didn’t matter whether these were branded as Greenpeace protests or not. What mattered is that as many people as possible felt inspired to join in, and that together we win. Which we did: Shell canceled its Arctic oil exploration with no plans to return in the foreseeable future! In July 2015, Greenpeace activists took to kayaks and dangled from St. John's Bridge in Portland, Oregon, to stop the Shell Oil icebreaker Fennica from leaving port to support drilling operations in the Arctic. (image: Twelvizm/Flickr) Ultimately our goal is not to get "in the news" for the sake of it, but to make change. Sometimes being in the news is an important part of doing that, since it allows us to reach new or influential audiences. Other times, we make change behind the scenes. We use whatever tactic best advances the cause. HO: How bad will things get if we can't change corporate and public behavior? AL: First off, corporate behavior definitely has to change. The recent revelations about how terribly companies like Exxon and VW have lied to the world about climate change are inexcusable. It’s interesting that this question leaves off the need for political change though. Climate change has become such a politicized issue in America that our elected representatives are no longer able to act in a way that their moral compass and human compassion would naturally send them. The debate has been reduced to a playground argument of who’s right and who’s wrong. We don’t have time for this because things will get really bad if we don’t set aside our differences and start to tackle this together. There’s no question the climate is getting worse (the first six months of 2015 were the hottest on record), but public concern and engagement is also growing. The movement for climate solutions needs all kinds of people — students, artists, teachers, farmers, nurses, engineers, you name it. Whatever skill you have, the movement needs it. As temperatures rise, so do we. Originally published at Ensia.

This is an article by Marc Gunter. Marc Gunther and Twitter: @MarcGunther May 4, 2015 — Greenpeace rates tech companies on their data centers. Oxfam America ranks food brands on the sustainability of their supply chains. The League of Conservation Voters scores elected officials on their voting records. But who rates, ranks and scores Greenpeace, Oxfam America and the League of Conservation Voters? Or The Nature Conservancy, Conservation International or WWF? For now, no one. No independent organization has made a serious effort to evaluate the performance of environmental organizations. Nor, for that matter, do many environmental nonprofits report publicly on their effectiveness or admit their errors. Put simply, many green groups lack the accountability they demand from business and government. That’s a problem for donors, volunteers and staff members who want to spend their time or money doing as much good as they can for the planet. If, for example, you had US$1,000 to donate to help curb climate change, should you help The Nature Conservancy plant a billion trees by 2025, or support the fossil fuel divestment movement at 350.org or support the market-friendly partnerships of the Environmental Defense Fund? How could you decide where it would make the most difference? What’s more, and perhaps more importantly, measuring effectiveness and sharing findings would provide valuable information environmental groups could use to learn from one another’s successes, failures or insights. “Performance is a very hard problem for the nonprofit sector,” says Brett Jenks, the president and CEO of conservation group Rare. “It’s never in your best interest to outline failures. It’s never in a donor’s interest to admit they’ve made a bad investment. But it’s clearly in the public’s interest to better understand nonprofit performance.” Growing Pressures The encouraging news is that efforts are underway by big foundations and independent evaluators to better judge the effectiveness of all nonprofits, including green groups. Among the leaders in this movement is GuideStar, which harbors ambitions to become a Bloomberg-like information portal about nonprofits, to enable smarter decision-making by donors and NGOs alike. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation last year pledged US$3 million to help GuideStar bulk up its offerings. Jacob Harold, the 37-year-old president and CEO of GuideStar, is in the thick of the conversation about nonprofit performance. A Stanford MBA, Harold worked as a climate change campaigner for Rainforest Action Network and as a grant-maker focusing on effective philanthropy at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, so he’s thought a lot about how to measure the impact of environmental groups. It doesn’t make sense, he says, to try to devise a single metric or set of metrics to compare all green groups. But it might be possible to come up with ways to compare organizations within focus areas such as conservation, education, research or advocacy. Comparing one conservation group to another, or even comparing projects, is harder than it might seem, since it would require judgments about the relative value of, say, tropical rainforest, Rocky Mountain wilderness and suburban parkland.In fact, a coalition of conservation groups and their funders formed the Conservation Measures Partnership more than a decade ago to seek better ways to measure and improve performance of nonprofits focused on conservation. “There’s increasing pressure to show that spending leads to measurable outcomes,” says Nick Salafsky, co-founder and co-director of Foundations of Success, which manages the partnership. “Accountability is coming.” But comparing one conservation group to another, or even comparing projects, is harder than it might seem, since it would require judgments about the relative value of, say, tropical rainforest, Rocky Mountain wilderness and suburban parkland. The partnership has yet to introduce tangible tools for measuring whether and how much conservation organizations create change. Evaluating the effectiveness of advocacy groups is even harder than evaluating conservation groups because of, as Steven Teles and Mark Schmitt wrote in Stanford Social Innovation Review, “the complex, foggy chains of causality in politics, which make evaluating particular projects — as opposed to entire fields or organizations — almost impossible.” But that hasn’t stopped people from trying. Michael Bloomberg, the former New York mayor who made his fortune in the data industry, gave $80 million to the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, but only after insisting that the organization set targets and timetables for itself. “Bloomberg wanted the group to create better ways of gauging the success of its efforts,” Politico reported. “We can’t let the difficulty of measuring advocacy stop us from trying.” – Jacob Harold Insiders often have a sense of which groups perform well and which do not. That’s the impetus behind Philanthropedia, a crowdsourcing website (acquired in 2011 by GuideStar) that collects opinions about non-governmental organizations from experts much as Amazon collects critiques from book reviewers. The effort remains a work in progress, but some of the anonymous reviews of green groups can be insightful. “We can’t let the difficulty of measuring advocacy stop us from trying,” Harold says. The largest and most influential evaluator of nonprofits, Charity Navigator, has by its own admission yet to venture into the realm of measuring results. The organization rates charities on two metrics — financial health and accountability/transparency — that are useful for spotting fraud or waste but don’t get to the key question of performance, its former CEO, Ken Berger, told me recently. Setting Goals and Timetables How can green groups be more explicit about their goals and whether they have achieved them? Charting Impact — a project of GuideStar, the BBB Wise Giving Alliance and Independent Sector — has developed five deceptively simple questions designed to promote self-reflection and examine organizational missions, results and goals. They encourage nonprofits to answer them and publish the answers. The questions are:

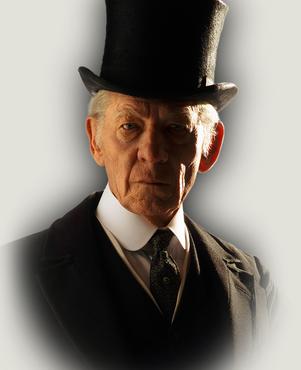

Since Charting Impact became part of GuideStar’s database about 18 months ago, about 5,000 nonprofits have answered the questions — out of about 105,000 that provide information to GuideStar. Five Snapshots Here are snapshots of how five environmental groups are measuring their impact: The Nature ConservancyFY2014 revenues: US$1.1 billionA decade ago, as part of an initiative called Conservation by Design, The Nature Conservancy pledged that by 2015 it would “work with others to ensure the effective conservation of places that represent at least 10 percent of every major habitat type on Earth.” How’s that going? Unclear. TNC’s latest annual report makes no mention of the goal, which receded after Steven McCormick, the CEO who set it, left. Today, as a sprawling, global organization with staff in hundreds of communities, and five key initiatives — land, water conservation, ocean conservation, climate change and sustainable cities — TNC resists simple characterization. “We’re kind of like GE,” says chief external affairs officer Glenn Prickett. “We’ve got a bunch of business lines, and we want to be the best at all of them. They can’t be consolidated into a single yardstick.” The group is developing a set of new goals, he says, to reflect its broader strategies. Prickett adds: “I don’t know if any of the conservation groups have a strong enough culture of evaluation.” OceanaFY2013 revenues: US$45.2 millionEstablished in 2001 by a group of foundations, Oceana says it is “dedicated to achieving measurable change by conducting specific, science-based campaigns with fixed deadlines and articulated goals.” Its chief executive, Andrew Sharpless, says: “We set the deadlines for getting policy outcomes, and those deadlines are never more than five years after we start a campaign.” In 2013, for example, the Chilean government announced its first set of science-backed fishing quotas for four critical species of fish: common hake, anchoveta, sardines, and jack mackerel. This followed years of campaigning by Oceana, along with local scientists and activists. Currently, Oceana is running a seafood fraud campaign that aims to establish a traceability system for the U.S. seafood supply that tracks fish from boat to plate, keeps illegal fish out of the supply and provides consumers with more information about the seafood they purchase. The group says it hopes to achieve that by 2017. New policies, though, don’t necessarily translate into changes on the ground — or in the water. Laws need to be enforced. So, Sharpless says: “We are now reporting to the board on whether we see more fish in the ocean, in the places we are campaigning. That’s the best possible way to measure our impact.” Those reports are not public, at least not yet. Greenpeace USAFY2013 revenues: US$33 millionAnnie Leonard, who became executive director of Greenpeace USA last year, says the question of which environmental groups are most effective is “almost an unanswerable question. Most effective? Most effective at what?” For its part, Greenpeace USA intends to build a stronger environment movement. “We have so much science, we have so much data, we have so many economic studies, but are we building power?” Leonard asks. Twenty million people participated in the first Earth Day in 1970, she notes, and major legislative victories followed. Greenpeace USA wants its members to do more than sign a petition or make a donation. “Our new slogan is, you’ve signed up, now you’ve got to show up,” Leonard says. “We are doing lots of rigorous, ambitious, extensive testing around the question of how we get people more engaged in the our movement.” So far, though, Greenpeace USA hasn’t set any specific, public goals, so its progress will be hard to measure. Chesapeake Bay FoundationFY2014 revenues: US$30.6 millionPerhaps because it is dedicated to a single body of water — albeit a body of water that depends upon a 64,000-square-mile watershed that spreads across six states — the Chesapeake Bay Foundation has a clear goal: To save the bay, which it defines as reaching a score of 70 on CBF’s Health Index, a comprehensive measure incorporating data about water quality, pollution, habitat and fisheries. Currently, the index stands at 32, up from the low 20s back in the 1980s. It’s the equivalent of a D plus, according to Will Baker, the foundation’s president. “Hardly what your mother would be happy with, but we’re going in the right direction,” he says. All of CBF’s varied activities — lawsuits, lobbying, restoration projects and educational programs — are designed to improve the bay’s health. Having a specific goal “has paid dividends for us in terms of focus, in terms of asset allocation and in terms of being able to raise the funds to support our work,” Baker says. RareFY2014 revenues: US$17.5 millionAn unusual conservation group, Rare works with partners in the developing world to run marketing campaigns, called Pride campaigns, that are intended to inspire communities to protect their natural resources. It is explicit about its theory of change and tracks the results of campaigns, not just in terms of changed attitudes, but in terms of the health of the species or habitat being targeted for protection. The group has helped organize more than 250 campaigns in more than 50 countries. Ongoing campaigns are rated red, yellow or green, according to Brett Jenks, Rare’s president and CEO. The ratings are used to allocate resources and to evaluate staff members, and they are shared with its staff and board, but not the public. “You know which ones work well because those are the ones on the front page of the website,” he jokes. Being more public about projects that fall short of expectations would discourage bold bets, he explains. One of the risks of public reporting on successes and failures is that groups could choose to play it safe. “In your quest for efficiency, you don’t want to wipe out the potential to waste some money on the road to creating a big impact that the world needs,” Jenks says. None Too Soon For anyone who cares about the environment, the ongoing efforts to improve effectiveness, accountability and transparency — however imperfect — can’t come too soon. Without them, it’s all but impossible to know whether all the money flowing into green groups is having the impact it should. In his new book, Michael Shuman debunks many of the myths around economic development. By Hannah Onstad This was originally published on Alternet.org Think local. Buy local. Support your local community. Community investment. This all makes sense, right? Right. Then why do so many government-funded economic development programs get this wrong? According to community economics advocate Michael Shuman, mainstream economic development today is a scam. States and local government agencies spend big money to lure corporations to their region but do little to stimulate the local economy or support local businesses. And those small businesses, not the chain stores, are often what give a neighborhood its unique identity and make it desirable to live in. In his new book, The Local Economy Solution: How Innovative Self-Financing “Pollinator” Enterprises Can Grow Jobs and Prosperity (Chelsea Green, June 2015), Shuman debunks many of the myths around economic development—that tax breaks for wealthy corporations are beneficial for all, that only big businesses create jobs, that consumers only care about price, and that social enterprises can't be self-financing. Shuman, who has been a leader in the local economy movement for more than two decades, proposes low-cost pollinator businesses to stimulate the local economy through small business development. He defines a pollinator as a self-financing business with a mission of supporting other local businesses. Pollinators lead to more dollars spent within that community, and often favor atriple bottom lineapproach that makes a connection between the three Ps: people, planet and profits. Unlike impersonal chain stores, local pollinator businesses foster more connection between consumers and retailers, food growers and customers, and businesses and their employeesm, resulting in a healthier, more equitable community, which translates into safer neighborhoods that can weather economic fluctuations. Without easy access to economic development funds, pollinator businesses rely on a DIY ethos and the sharing economy, which includes cross-selling with other like-minded businesses, cost-savings through collectively buying goods and services, and being creative with financing. The book offers models for how effective self-financing pollinator businesses work, making it a must-read for anyone interested in starting a local business. Yet the common thread among these pollinators is the creativity of the entrepreneurs who start them. From a clever, low-cost “Shift the Way You Shop” campaign that promotes consumer awareness about buying local, to a program that supports farmers in Paraguay with microlending, where small loans make a big difference, Shuman sees a revolution underway. He identifies five types of pollinator businesses: planning (business planning), purchasing (collective buying), people (training and mentorship), partnering (networks) and purse (financing) and shares business models for each type, from retail shopping networks and pay-it-forward food cooperatives to startup accelerators and credit unions. Kimber Lanning, founder of Local First Arizona, is just one of the many entrepreneurs who's changing hearts and minds. She's been instrumental in influencing how Arizona state procurement offices contract with suppliers. Lanning created a study showing that for every $100 in office goods sourced from national chain Staples, $5 was respent within the state. In contrast, for every $100 spent on the same goods purchased from a local vendor, $33 was respent within the state, demonstrating how profits earned locally recirculate in the region. Another example of a pollinator is Impact Hub; with more than 68 locations in 49 countries, this co-working space and business incubator is jumpstarting other social enterprises by housing startups where entrepreneurs gain access to workspace, mentors and financing. “We’re a hybrid pollinator,” says Kristin Hull, co-founder of Impact HUB Oakland. “We hire people from Oakland, and we also help startups in Oakland by providing resources, education and connecting people, as well as a creative and supportive space to work.” Impact HUB Oakland was one of the first tenants in a renovated historic building project called the Hive, which offers a mix of retail, housing and office space and features a honeycomb with the word "hive" painted on the facade. Some of the earliest examples of pollinators focused on coupons, likeChinook Book, a printed guide packed with discounts to local merchants, now sold in five different U.S. markets. Merchants sell the book in their stores and each book provides discounts totaling more than the cost of the purchase price, making it an easy sell for consumers who can quickly earn back the cover price in discounts. Chinook's business values dictate that it only include companies that "treat their employees and suppliers well, minimize their environmental impact, and support the community that supports them." More financially creative pollinators include Bernal Bucks, created by Arno Hesse and Guillaume Lebleu, which started as an alternative community currency in the Bernal Heights neighborhood of San Francisco and evolved into what's thought to be the first of its kind debit card, which can be used wherever debit cards are accepted, but with incentives for using it locally. Card holders earn 5% of their purchases back in Bernal Bucks when frequenting one of the participating community businesses, plus they earn $10 in Bernal Bucks for every $200 spent with the card (one Bernal Buck is equal to $1). While some of the suggestions are easy to accomplish, such as moving your savings to a local bank or credit union, others require more startup effort such as creating a local mutual fund or spreading self-directed IRAs. Still, Shuman inspires with what's possible. Once you begin to understand how pollinators work, you might begin to see examples in your own neighborhood. Take Melissa Davis and Kristen Loken's beautifully produced, coffeetable-worthy book This is Oakland: A Guide to The City's Most Interesting Places. Lavish photographs of unusual, local shops and coveted restaurants pair with short profiles, all organized by neighborhood, making this a must-have for Oakland natives as well as newcomers. It's easy to see how promoting these foodie destinations, hip artisans and colorful retailers serves to further establish Oakland as a desirable place to live and work, and attracts further investment to the city. Many of the retailers in turn sell the book, so it has a built-in distribution network. Many people hit hard by companies downsizing, outsourcing and automating, and simply failing to recover the jobs lost during the recession, would do well to look locally for solutions, whether starting a local business or working for one. Ernesto Sirolli, a business counselor with a popular TEDtalk who's mentioned in the book, sees more women, downsized older workers and younger people starting their own businesses. There are signs this trend is happening globally. Paul Mason of the Guardianwrites: “Almost unnoticed, in the niches and hollows of the market system, whole swaths of economic life are beginning to move to a different rhythm. Parallel currencies, time banks, cooperatives and self-managed spaces have proliferated, barely noticed by the economics profession, and often as a direct result of the shattering of the old structures in the post-2008 crisis.” One could say Shuman saw this coming. As a founder of BALLE, Business Alliance for Local Living Economies, Shuman has worked to shed light on how forging connections at the local level, between investors and entrepreneurs, businesses and communities, eaters and farmers, is beneficial for everyone. With all of this activity it would seem state and local economic development offices would be eager to latch on to the trend and engage smaller, locally owned businesses. But so far that hasn't been happening, forcing local businesses to bootstrap themselves. So, just how do state and local agencies spend those seemingly scarce economic development dollars? According to Shuman, many focus on “attract and retain” schemes that incentivize large companies to relocate to an area in the hope of creating local jobs. These incentives are paid for with taxpayer dollars, and often involve wining and dining corporate representatives and competing with other states to win the bid with large payouts—including tax incentives, property development giveaways and cash incentives for job creation. Shuman cites a boondoggle in Sarasota County, Florida where officials were poised to cough up $137 million in incentives in an effort to woo a Danish pharmaceutical company to relocate, in spite of the fact the move would only create 191 local jobs. In the end, the region lost out to a neighboring state that offered an even better deal. Shuman believes even if a company accepts incentives and relocates, the community rarely benefits. That’s because the incentives offer a terrible return on the dollar, sometimes with tens of thousands of taxpayer dollars spent to create each job. Other times, the jobs just don’t materialize as promised, or the company’s existing workers relocate. What’s worse, the revenue generated by the company often leaves the area, heading back to corporate offices and senior executives, doing little to stimulate the local economy. After a while, the company, which has no real geographic loyalty, picks up and leaves when its incentives run out. Sometimes the new business even displaces an existing local business, because unsubsidized local businesses are hard pressed to compete with subsidized non-local ones. The economic incentives actually work to undermine the local businesses they should be supporting. The thrust of The Local Economy Solution is not about changing the traditional economic development model as much as how to innovate to prosper. The goal, according to Shuman, should be to “minimize public subsidies and to find the lowest-cost ways of activating and spreading private sector businesses.” With the economy spluttering, hopefully more people will see the value in supporting their favorite local cafes, restaurants and shops at the expense of the chains, and realize that keeping more money in the community helps their friends and neighbors too. Shuman's book provides insight into the planning and consumer behavior shifts needed to make our cities and towns more resilient, safer and healthier, as well as real-world financial modeling for investing in, or starting a successful local business. There's no better incentive to be a pollinator.  Just how would the great Sherlock Holmes spend his golden years? Writer Mitch Cullin in his novel A Slight Trick of the Mind imagines Holmes living in virtual seclusion, struggling with the onset of Alzheimer’s and tracking his forgetfulness with marks in a diary to show his physician—rendering the infallible crime fighter a mere mortal confronted with his own frailty. His book is the basis for Mr. Holmes, a new film from Miramax directed by Bill Condon, and memory is the complicating factor for our hero as he strains to recall details of the case that still haunts him as as he takes stock of his life and begins to write his own account of it—a chance for Holmes to tell his side and where it departs from Watson’s. We also learn that the case in question is responsible for his decision to retire from his storied career to a remote English country house situated on the shore within view of the chalk cliffs where he lives with a housekeeper and her curious son who he befriends. This is a fitting setting, as he succumbs to old age in his garden tending bees, and consistent with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s His Last Bow. Ian McKellen is at his finest playing the distinguished Holmes who is transformed by this friendship with the 14 year old Roger (an exceptional performance by Milo Parker). McKellen’s virtuosity is apparent as he embodies a younger Holmes through flashbacks portraying his devotion to reason, and as we see later, a more compassionate and humane elder–the more humble man, not the myth. Unlike the more recent attempts to update Holmes for modern-day audiences with younger, more attractive versions (Robert Downey Jr. and Benedict Cumberbatch come to mind), the plot in Mr. Holmes is driven neither by typical action-drama nor cynical repartee, but rather the fierce deductive reasoning Holmes fans love and movie-goers will appreciate. Laura Linney as Mrs. Munro does Mr. Holmes the service of balancing the loftier pursuits of the detective with her more grounded concerns about earning a living and raising a child, allowing her character to shine as she adds pointed tension to the plot. Mr. Holmes will delight true fans and intrigue casual viewers with an intensity and depth revealed in a character we thought we knew. A fitting end to a monumental franchise—at least for now.  By Hannah Onstad OK, admittedly this was my first experience with the croissant-donut merger we've all been hearing so much about. Something just came over me today and I had to a try the cronut or the cron't as it is popularly called at donut savant. All I can say is, if you have an addictive personality, cron't even go there (sorry!) It's hard not to love. Flaky yes, moist, yes, though a bit denser...hardier than a croissant, and more reminiscent of childhood and my favorite local bakery, Judicke's in Bayonne, N.J. (so iconic the NYTimes managed to cover the Judicke's experience!). True, Judicke's specialized in the Polish specialty chrusciki (crhis-CHICK-ee) which were twisted and fried dough doused with powdered sugar. I, however, was a devoted fan of the many-colored sprinkled donuts, and was known to consume more than one, sitting at Aunt Regina's circular formica table. And later in high school, after hitting the deli, I'd make my way to Judicke's salivating for that first bite, gently breaking the sweet-smelling gooey icing, while my teeth sank into the fluffy-cake. Mmmm... The cron't is different, mysterious even. I ordered the dark chocolate topped cron't. The icing is just right, sweet but not overly so, nor glumpy and teeth-coating like a Dunkin Donuts monstrosity. The cron't's flakiness is kind of subtle, it hits the brain but doesn't fully compute. What is this neither-croissant-nor-donut-thing I'm eating? Yet, immediately, one appreciates its essence, however fleeting. It disappears quickly, I found I had to order another. Just to be sure. This time I went for the maple gluten-free donut while my son nailed the S.O.S. (think jelly donut meets danish). His was superior in every way. While I appreciate that the gluten-free option was available...it was...not the same. There are many other choices: the Apple Fritter was rather yummy in a lightly-soaked, sweetly-hardened-icing sort of way. Still, it's rare for me to set out on a donut quest these days. I remember bringing a dozen donuts to my Berkeley office once a few years back and getting seriously chastised. It was as if I brought Velveeta to a wine tasting. Oh, how times have changed! With a spate of new options in Oakland including organic donuts, vegan donuts, gluten-free donuts, the aforementioned cron't, not to mention the injectable-experience from Doughnut Dolly one can say that the donut is finally having its moment—carpe diem! I intend to try them all. By Hannah Onstad

Originally published by AlterNet.org) In today’s digital gold rush, microtask workers are getting paid, though possibly shortchanged. Waves of outsourcing have been killing manufacturing and call center jobs here in the U.S. for decades. Now a class of lower-paid tech workers may be working themselves right out of a job. In 2005, Amazon launched the Mechanical Turk Service, a service marketplace where humans perform microtasks that computers don’t do as well as humans...yet. Microtasks are small units of work that require human decision-making—things like identifying objects in photos, writing short descriptions, translating text from one language to another, and identifying emotion in written text. With 500,000 Turkers, as they are known, in 190 countries, some willing to work for as little as $1.38 an hour, they represent a huge informal workforce. Read More

|

About this BlogWritten by Hannah Onstad, unless specified otherwise. Occasionally, posts here have been previously published elsewhere, and if so, that is noted at the top. Archives

June 2020

Categories |